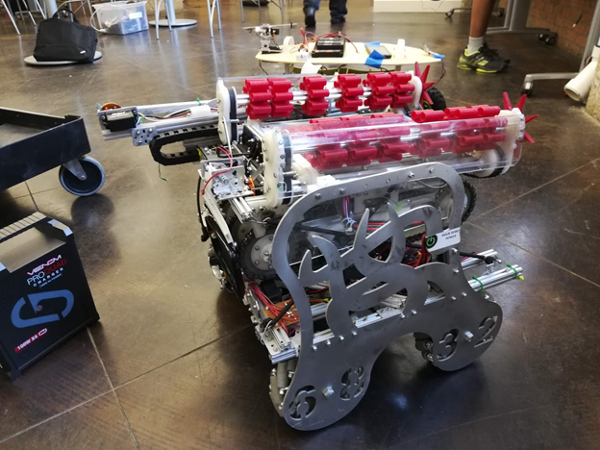

Id wouldn’t suspect that most mining ASICs have kept “post mining” applications into consideration at all to be fair. Additionally, even the most advanced tools only get you most of the way when there’s this many signals in such a small area that you keep having to tweak due to crosstalk issues the tools can’t take into account. Speaking from experience with Zynqs and DDR4, short of any rf applicaitons, DDR routeing is definitely the most difficult poriton of the design in these cards and getting correct length matching is very important. In short, if you want every marginal card you build to work with every marginal bin of chip (both fpga and ddr), you need to take a very close look at these things. It basically ends up a literal pile of spaghetti trying to keep all the lengths matched but having varying degrees of distances to cover. Additionally, you’re definitely going to have some ringing and crosstalk on every line with all these ~100+ signals bunched together in a very small space so you have to keep the lengths matched even tighter to allow more margin for this. with the different geometries of the chips (destination and source). These DDR3 busses are on a zynq 7000 so they’re likely at least 64 wide (maybe 72 ECR) so you have match the data lines, address lines, control lines, length fairly close. DDR operates at a “Double Data Rate” and not deferentially, so while the actual speed itself isn’t the most important, the Data is clocked on both the falling and rising edge of each clock cycle and has to be lined up very close while being measured in the nano-picoseconds range (for the edge slew rate combined with setup-hold time, not data rate). I just want to comment that this is not exactly correct. Posted in ARM, FPGA Tagged ASIC, bitcoin mining hardware, cryptocurrency, fpga, repurpose Post navigation We’re not sure the if the EBAZ4205 will enjoy the same kind of popularity in its second life, but the price is certainly right. When IT departments started dumping their stock of Pano Logic thin clients back in 2013, a whole community of dedicated FPGA hackers sprouted up around it. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen FPGA boards hit the surplus market at rock bottom prices. Once you’re done, you’ll have a dual core Cortex A9 Linux board with 256 MB DDR3 and a Artix-7 FPGA featuring 28K logic elements to play with. You’ll also need to add a couple diodes to configure which storage device to boot from and to select where the board pulls power from. For one thing, you may have to solder on your own micro SD slot depending on where you got the board from. The Zynq SoC combines an FPGA and ARM CPU.Īccording to, it takes a little bit of work to get the EBAZ4205 ready for experimentation. Since it’s just the controller it won’t help you build a budget super computer, but there’s always interest in cheap FPGA development boards.

Known as the EBAZ4205, this board can be purchased for around $20 USD from online importers and even less if you can find one used.

While it won’t teach an old ASIC a new trick, has documented some very interesting details on the FPGA control board of the Ebit E9+ Bitcoin miner. Naturally, hackers are hard at work trying to find alternate uses for these computational powerhouses. But eventually even the most powerful mining farm will start to show its age, and many end up selling on the second hand market for pennies on the dollar. While an array of high-end GPUs is still viable for some currencies, the real heavy hitters are using custom mining hardware that makes use of application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) to crunch the numbers. For anyone serious about mining cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin, we’re well past the point where a standard desktop computer is of much use.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)